Real-time imaging of contact between cells and between a single neuron’s extensions

Researchers from The University of Osaka report two new fluorescent indicators that can be used to visualize dynamic contacts between cells and between extensions of the same neuronal cell in real-time

Osaka, Japan – Living organisms are made up of hundreds of thousands of cells that cooperate to create the organs and systems that breathe, eat, move, and think. Now, researchers from Japan have developed a new way to track how and when cells touch each other to work together in these ways.

In a study published in January in Cell Reports Methods, researchers from The University of Osaka reported the development of fluorescent markers for monitoring cell communication under a microscope.

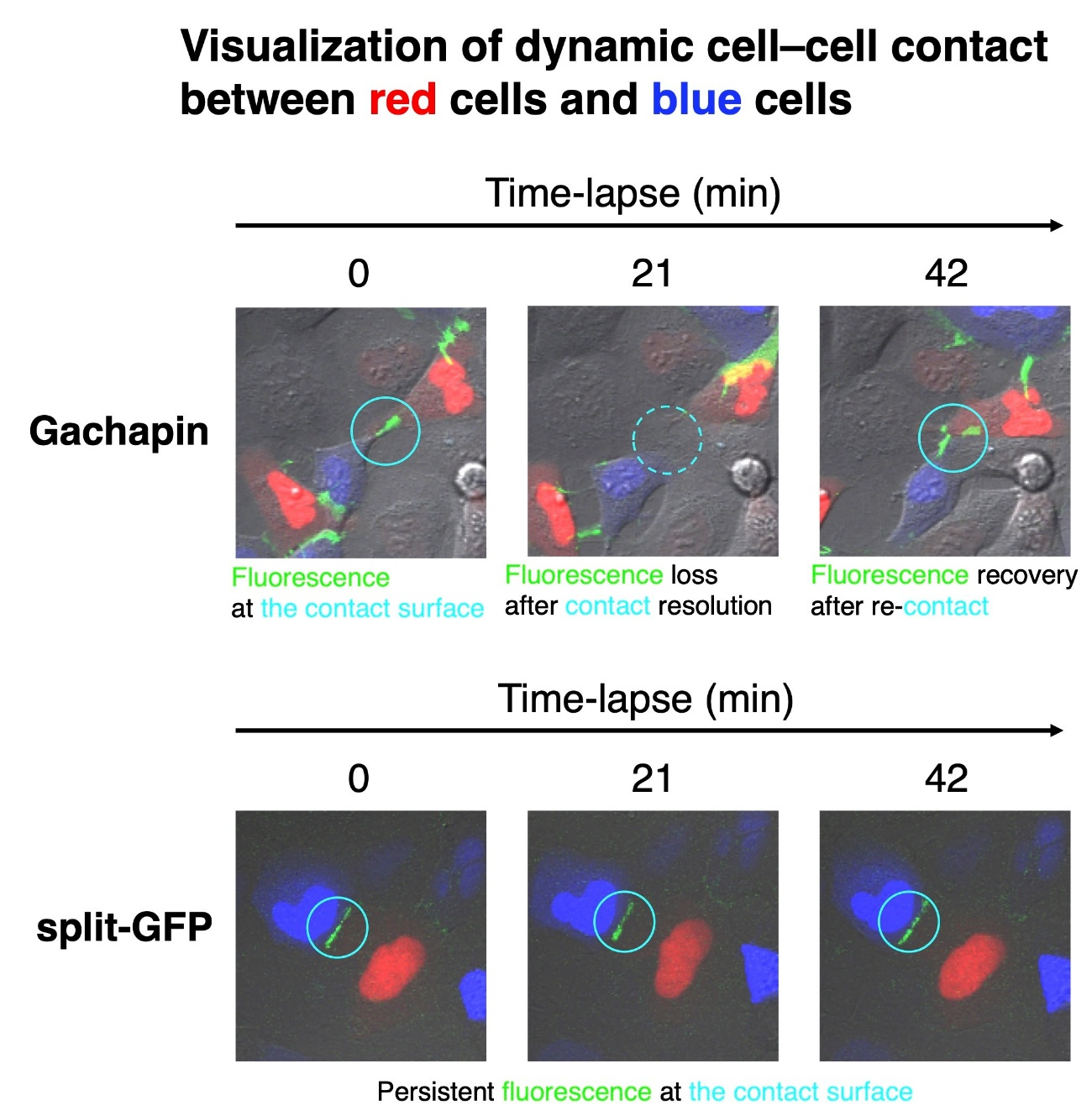

Cells communicate with each other by making cell-to-cell contacts, and fluorescent markers are often used to visualize these contacts. The most commonly used marker for this purpose is green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP can be divided into two halves that are expressed on different cells. When the cells touch, the two halves come together to form a complete GFP, letting off a fluorescent signal.

“Split GFP is useful for detecting the formation of stable connections between cells,” says lead author of the study Takashi Kanadome. “But because it takes time for the rejoined GFP to emit its signal and the association is irreversible, this approach cannot be used to detect dynamic cell–cell interactions in real-time.”

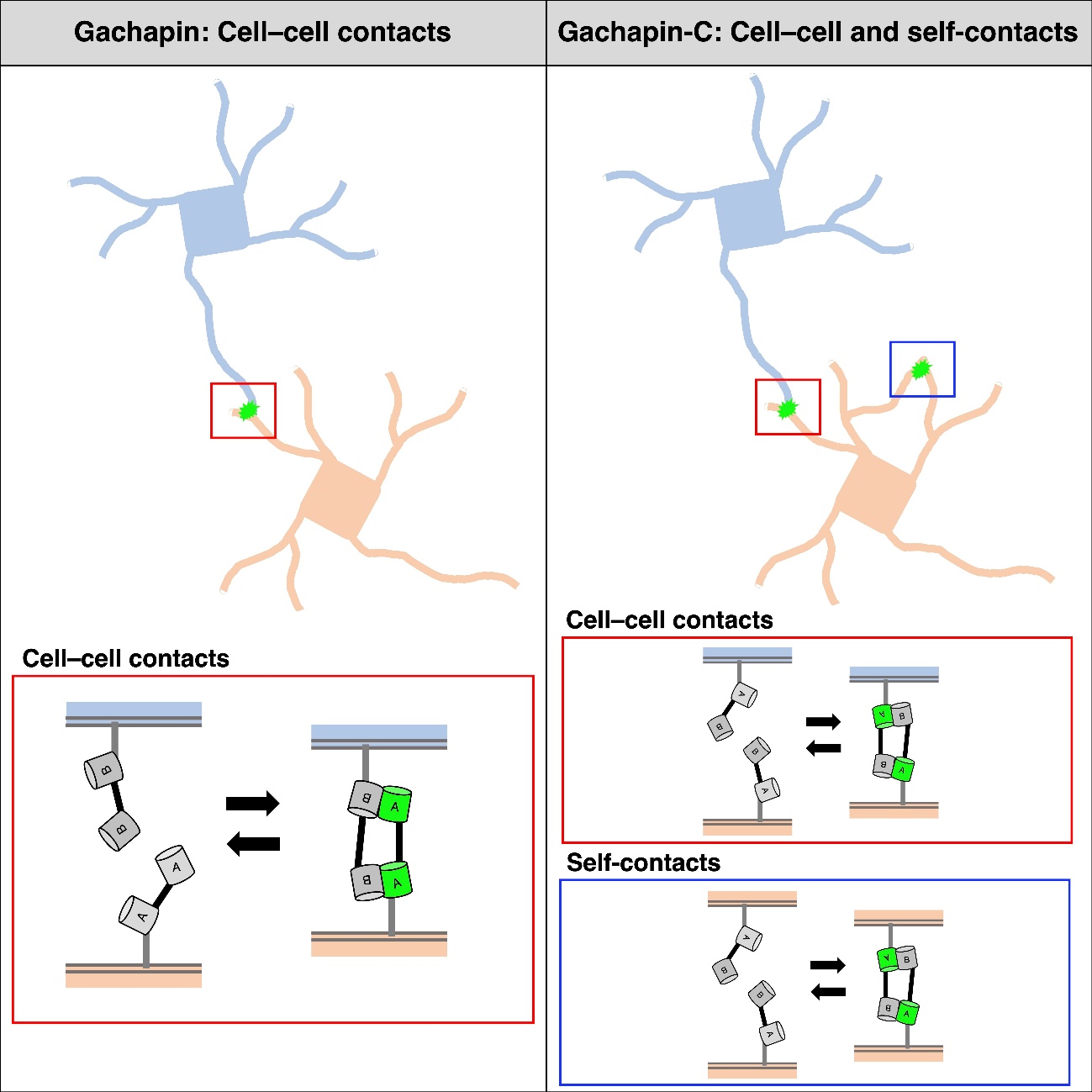

To address this, the researchers developed a new fluorescent marker called Gachapin. It has two parts: a fluorescent marker part that remains dark unless it is next to its binding partner, and a binding part that activates the fluorescent part upon close proximity. Because the binding part acts as an on/off switch for the fluorescent marker, Gachapin lights up quickly when cells touch and then turns off when the cells move apart.

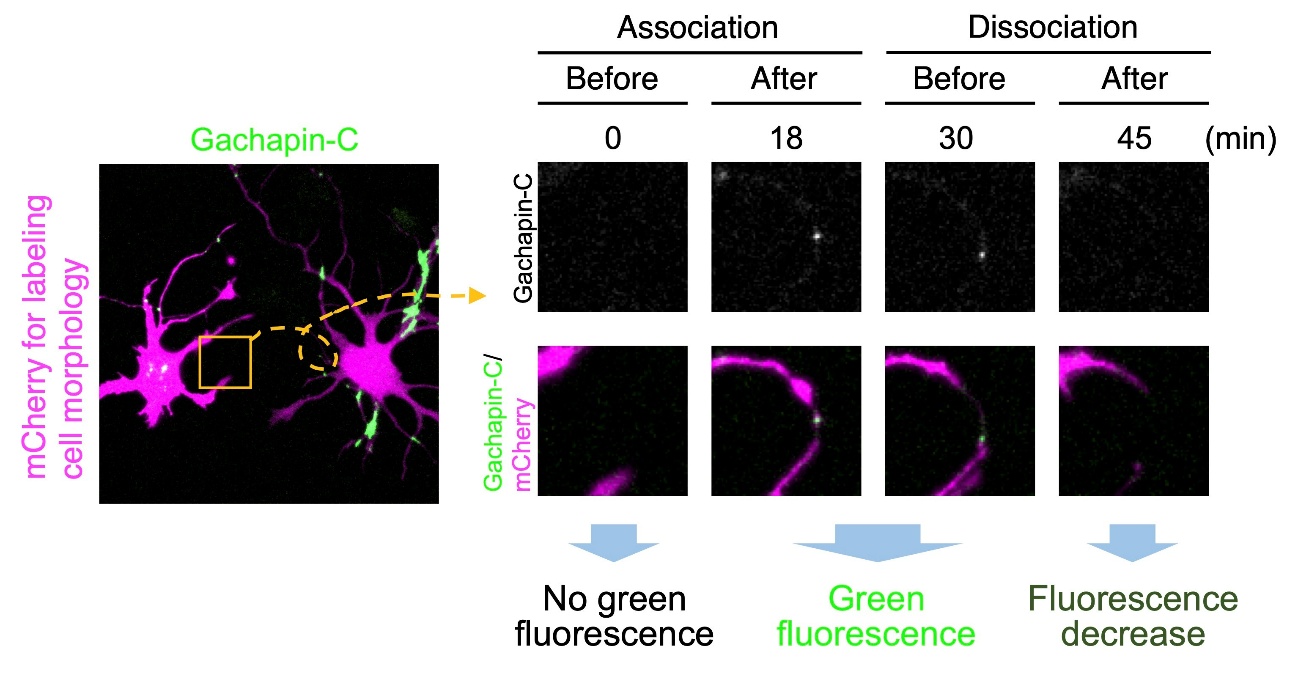

“Using Gachapin, we were able to detect the rapid formation and disruption of temporary, reversible cell–cell contacts,” explains Takeharu Nagai, senior author. “Excitingly, when we used time-lapse imaging, we were able to watch neuronal processes, which are long, thin extensions for communicating, form contacts with processes on adjacent neurons in real-time.”

In addition to the two-component Gachapin, the researchers developed a single-component version called Gachapin-C. When expressed in neurons, Gachapin-C not only lit up when different cells touched, it also let off a fluorescent signal when processes from the same neuron contacted each other.

“These two fluorescent indicators, Gachapin and Gachapin-C, dramatically improve our ability to visualize and understand how cells interact with each other,” says Kanadome.

This study shows that rapidly activated one- and two-component fluorescent indicators can be used to monitor complex patterns of connectivity among a variety of cell types, including neurons. In the future, Gachapin and Gachapin-C are expected to advance neural circuit research and could help clarify the role of dynamic cellular interactions in brain disorders, leading to the development of new treatments.

More Information

Title: Fluorescent indicators for visualizing dynamic contact between cells and between processes originating from a single cell

Journal: Cell Reports Methods

Authors: Takashi Kanadome, Natsumi Hoshino, Susumu Jitsuki, Hidehiko Hashinmoto, Takeshi Yagi, and Takeharu Nagai

DOI: 10.1016/j.crmeth.2025.101292

Funded by: Japan Science and Technology Agency

Article publication date: 23-JAN-2026